Screw-Type Downhole Drilling Tools — Basic Knowledge

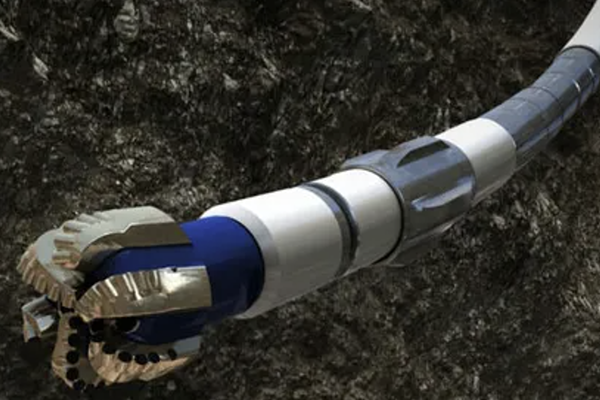

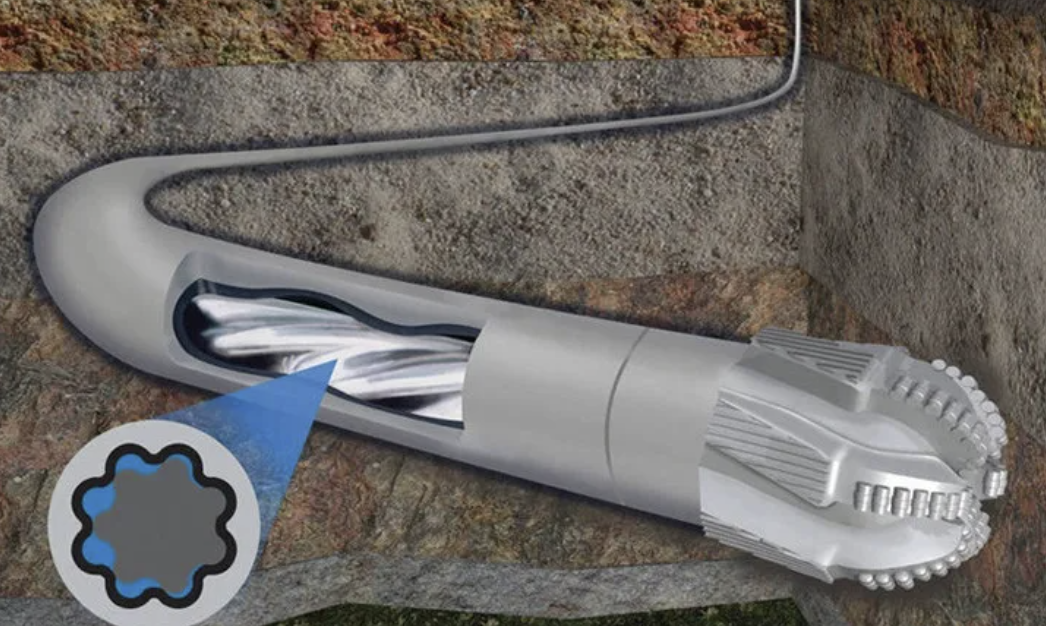

Overview A screw-type downhole drilling tool is a volumetric, downhole power tool that uses drilling fluid (mud) as its power source, converting hydraulic energy into mechanical energy. Mud pumped from the surface passes through a bypass valve into the downhole motor. A pressure differential between the motor inlet and outlet causes the rotor to rotate inside the stator. The rotor’s speed and torque are transmitted through a universal joint (flex shaft) and a drive shaft to the drill bit, enabling drilling.

Main Components A screw-type drilling assembly consists primarily of four major assemblies: the bypass valve, the mud motor, the universal joint, and the drive shaft.

Mud motor The mud motor is the primary component. Field experience and theoretical analysis indicate that, for normal and reliable operation, the pressure drop per motor stage should ideally not exceed 0.8 MPa; otherwise fluid leakage occurs, rotor speed drops rapidly, and in severe cases rotation can stop and the motor may be damaged. (One motor lead equals one stage.) The mud flow used in the field must be kept within the recommended range; flows outside that range reduce motor efficiency and increase wear. The motor’s performance parameters define the main performance of the entire drilling assembly. The motor’s theoretical output torque is proportional to the motor pressure drop, and the output rotational speed is proportional to the input mud flow. As bit load increases, rpm falls; therefore by monitoring surface pump flow and pump pressure (via the standpipe pressure gauge) the downhole torque and speed can be inferred and controlled.

Bypass valve The bypass valve is composed of a body, sleeve, valve element (core) and spring. Under pressure the valve element slides inside the sleeve, and its position changes the fluid path to provide two states: bypass (open) and closed. During run-in or tripping, the sleeve and body ports are open so mud bypasses the motor and flows into the annulus. When mud flow and pressure reach the valve’s set point, the valve element moves down and closes the bypass port; mud then flows through the motor, converting hydraulic energy to mechanical energy. If flow becomes too small or pumping stops, the spring pushes the valve element up and the valve reopens so mud again bypasses the motor.

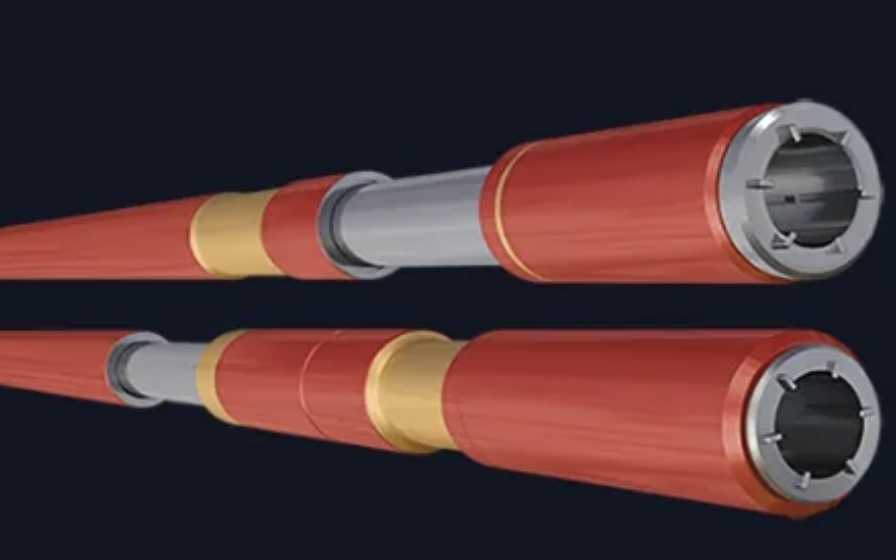

Motor construction and behavior The motor consists of a stator and rotor. The stator is produced by bonding a rubber liner to the inner wall of a steel housing; its inner bore is a helix with defined geometry. The rotor is a hardened steel screw. Rotor and stator mesh to form helical sealed chambers by virtue of their lead differential, enabling energy conversion. Rotors may be single- or multi-lobed (single-head or multi-head). Fewer lobes produce higher speed but lower torque; more lobes produce lower speed and higher torque.

Universal joint The universal joint converts the motor’s planetary (eccentric) motion into steady rotation of the drive shaft and transmits motor torque and speed to the drive shaft and bit. Flexible-shaft types are commonly used.

Drive shaft The drive shaft transmits rotary power from the motor to the bit and must also carry axial and radial loads generated by weight on bit and formation contact.

Operating Requirements

Drilling fluid requirements Screw-type motors can operate effectively with a variety of drilling fluids, including oil-based muds, emulsions, water-based bentonite muds, and even relatively clean water. Mud viscosity and density have little direct effect on motor performance but directly affect system pressures. If the pressure at a recommended flow exceeds the pump’s rated pressure, the flow should be reduced or the pressure drop across the motor and bit should be lowered. Solid particles such as sand accelerate wear on bearings and the motor stator, so solids content must be kept below 1%. Each motor model has a specified input flow range where efficiency is good; the mid-point of that range is generally the optimal operating flow.

Mud pressure and pump-pressure control When the motor is off-bottom and the flow is constant, the pressure drop across the motor remains constant. As the bit contacts bottom and weight on bit increases, circulating pressure and pump pressure rise. The driller can use: On-bottom pump pressure (while drilling) = Off-bottom circulating pump pressure + motor load pressure drop. Off-bottom circulating pump pressure is the pump pressure when the motor is off-bottom (also called the free-off-bottom or circulation pump pressure). It varies with well depth and mud properties, so it is not a fixed constant. In practice, it is sufficient to use the off-bottom pressure measured just after a stand is picked up as an approximate value for control calculations. When on-bottom pump pressure reaches the motor’s recommended maximum, the motor produces its optimal torque; further increases in weight on bit will raise pump pressure and, if the maximum design pressure is exceeded, the motor may stall. In that case the driller must reduce weight on bit immediately to prevent internal damage.

Handling and Use

General notes before first use Threaded connections between components are factory-prepared with anaerobic adhesive and torqued to specified values; re-torquing before first use is not normally required.

Surface inspection before running in hole

Lift the assembly by the lifting sub and place it into the rotary table so the bypass valve is located above the table and easily observed. Install the safety slips and remove the lifting sub.

Check bypass valve operation: press the valve element down with a wooden stick and release; the spring should return the element smoothly. Repeat 3–5 times to confirm there is no sticking.

With the bypass port below the rotary table, start the pump briefly: the bypass port should close, the motor should start and the drive joint should rotate. After stopping the pump, the valve element should reset and mud should discharge through the bypass port, indicating normal function.

Running the motor in hole

Strictly control running speed to avoid rapid descent that could cause the motor to reverse and unscrew internal threaded connections, and to prevent damage when passing through sand bridges, casing shoes or ledges.

In deep or high-temperature sections, and when passing unconsolidated sand zones, periodically circulate mud to cool the motor, protect the stator rubber, and prevent sand packing.

Slow the run as the motor approaches bottom; circulate ahead of final placement, starting with low flow until drill cuttings return to surface, then increase flow as needed.

Do not jar the motor into bottom or allow it to sit stationary on the bottom.

Drilling with the motor

Clean the hole bottom thoroughly and measure the off-bottom circulating pump pressure before beginning drilling.

Apply drilling weight gradually at the start. Use the pump-pressure relation above to control drilling operations.

Do not drill too fast at the outset; the motor, bit and hole bottom are “tight” and inadequate hole cleaning can cause bit balling.

Motor torque is proportional to motor pressure drop; increasing weight on bit increases motor load and thus motor pressure drop and torque.

Smooth and uniform rate of penetration and stands of drill string help maintain borehole inclination control and directional accuracy.

Pulling out of hole and inspection

Flush the bypass valve with clean water and work the valve element up and down with a wooden stick until it closes reliably.

Grip the assembly with a pipe wrench, rotate the drive-joint clockwise with a chain wrench while injecting clean water through the top of the bypass valve to flush the interior, then introduce a small amount of lubricating oil (mineral oil) into the motor.

Control pulling speed to avoid stuck pipe or damage to the motor.

Measure bearing clearance; if shaft bearing clearance exceeds allowable limits the motor must be repaired and bearings replaced. In re-entry or workover motors, axial bearing clearance should be adjusted as required.

Pre-run surface checklist (summary)

Thread locking compound is applied to all housings except the lifting sub-to-bypass valve connection.

Install the screw-type bit using the correct bit adapter. Use a chain wrench only on the drive-shaft end and rotate only counterclockwise (viewed from above) when making up to avoid loosening internal threads.

Lift the motor by the lifting sub and place it in the rotary; position the bypass valve where it can be observed, secure with slips and remove the lifting sub.

Check bypass valve sealing: press the valve element down and fill the bypass area with water from above. If the valve is tight there should be no significant drop in water level. Remove the stick; the valve element should pop up under spring force and water should flow evenly from the side ports — this indicates normal condition.

After running in, position the bypass valve where it is visible below the kelly/rotary. Start the mud pump and gradually increase flow until the bypass valve closes. Raise the motor slightly and observe whether the bit rotates; with the valve closed there should be no mud exiting the bypass. After stopping the pump, confirm the bypass reopens and mud discharges through the bypass ports. Do not raise the bypass valve above the rotary table while the pump is still running to avoid contaminating the rig floor.

Assemble any required bent subs, non-magnetic drill collars, stabilizers, etc., according to the designed assembly.

Running in the hole — additional guidance

Control descent rate to avoid damage from sand bridges, ledges or casing shoes. If such sections are encountered, circulate the mud and slowly ream open the hole before proceeding.

If bent subs or bent housings are used, the bit side may more easily contact the borehole wall or casing shoes; periodically rotate the assembly to reduce side-tracking effects.

For deep or high-temperature wells, perform intermittent circulation while running in to prevent bit plugging and to protect stator rubber from heat damage.

If mud does not flow quickly through the bypass port during descent, slow the run-in rate or pause periodically to fill the motor with mud. Do not jar or set the motor on bottom.

Starting the motor in hole

If the motor has been on bottom, raise it 0.3–0.4 m and start the mud pump. Record the standpipe pressure and compare it with hydraulic calculations. Slightly higher pressures are normal because of side-loading of the bit.

Clean the hole bottom thoroughly, especially in directional wells. Accumulated cuttings affect rpm and may induce dogleg. Proper circulation while slowly rotating the motor (or rotating incrementally 30°–40° at a time) will clean bottom cuttings. After cleaning, raise the motor 0.3–0.4 m, check and record pressure values.

Re-enter bottom, gradually increase weight on bit; motor torque will rise and standpipe pressure will increase. The increase in standpipe pressure should correspond to the motor pressure drop values specified for the motor model. Monitoring this rise provides feedback that motor load and drilling weight are appropriate and that motor speed is stable. Keep standpipe pressures within the motor’s recommended limits so the driller can promptly evaluate tool condition.

If the motor is off-bottom and circulation pressure is high, the bit nozzles may be plugged or the drive shaft may be jammed.

Tripping out — precautions

While tripping out, the bypass valve is in bypass (open) state and allows drill fluid in the drill string to flow into the annulus, but the motor cannot discharge fluid by itself. It is common to displace the top of the drill string with heavier fluid before pulling the motor to ensure safe displacement.

After the motor reaches the bypass valve level at the rig floor, remove the bypass components and flush the motor with clean water from the top of the bypass valve. Use a wooden stick or hammer handle to work the valve element up and down until it moves freely. After cleaning, reattach the lifting sub and pull the motor out.

If on-site fresh-water washing is available, thoroughly flush the motor before storage.

If cleaning facilities are not available, secure the motor body at the rig floor, clamp and turn the large end of the drive shaft (the end that connects to the bit) with a hydraulic tong, rotating it clockwise (the same direction as downhole drilling rotation). This forces mud from the motor’s sealed chambers to be expelled and helps protect the motor from corrosion. This practice is especially important in winter to prevent residual mud inside the motor from freezing before the motor is run again.