Multidimensional Effects of Drill Rod Wall Thickness in Rock Drilling and Optimization Strategies

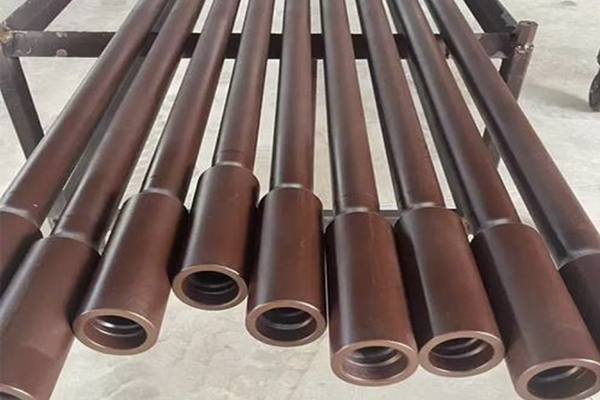

In rock drilling operations, drill rod wall thickness is a key parameter that affects quality, efficiency and cost. It is not just a dimensional specification: wall thickness influences rod strength and rigidity, hole accuracy, cuttings evacuation and energy consumption. Whether the selected thickness is appropriate will directly affect project progress and overall return. The following analyzes the specific effects across four core dimensions and outlines practical optimization directions.

Impact on drill rod strength and durability

Excessively thick walls: Greater wall thickness increases the rod’s load capacity and rigidity, improving resistance to axial loads and torsional stress. Thick rods are therefore better suited to hard rock and complex strata where deformation or fracture risk is high. Downsides include significantly higher self‑weight, which complicates handling and installation, increases loads on rigs and transport equipment (accelerating wear) and raises logistics and setup difficulty.

Excessively thin walls: Thin rods are lighter and easier to handle, reducing instantaneous load on supporting equipment and improving operational flexibility. However, reduced wall thickness means much lower strength and stiffness, making rods prone to bending, buckling or torsional deformation in service. In hard or heterogeneous formations this sharply increases the risk of fracture, shortens service life and forces more frequent replacements—driving up consumable and downtime costs.

Impact on drilling accuracy Hole straightness and size control are core engineering requirements, and wall thickness affects these by changing rod stability.

Thicker walls: Higher rigidity helps maintain a straight drilling path and reduces bending or deviation, supporting better hole accuracy. However, if the rod has concentricity or manufacturing defects, an overly thick wall can amplify eccentricity errors and negatively affect verticality and bore diameter, potentially exceeding tolerance limits.

Thinner walls: Lower stiffness makes the rod susceptible to elastic deformation and lateral vibration during rotary advance, which degrades hole accuracy. Typical consequences include uneven bore diameter, rough hole walls and poor alignment—problems that compromise subsequent casing, grouting or anchoring operations.

Impact on cuttings removal (flushing) Smooth evacuation of cuttings is essential for continuous drilling. Wall thickness alters the internal passage size and thus flushing efficiency.

Thicker walls: Increased wall thickness reduces the internal bore diameter available for flushing media (drilling fluid, compressed air), lowering conveyance capacity and causing cuttings to accumulate inside the hole. Cuttings build‑up accelerates bit wear, shortens bit life and can lead to stuck pipe or other interruptions that harm productivity.

Thinner walls: A larger internal passage facilitates faster removal of cuttings and better matches high‑efficiency flushing regimes. Yet thin walls are more vulnerable to abrasion from cuttings and fluid flow, which can erode the inner wall and cause structural damage. When inner wall wear occurs, flushing performance and operational continuity are also compromised.

Impact on energy consumption Wall thickness influences the load on drilling equipment and the continuity of operations, both of which affect energy use.

Thicker walls: Heavier rods require greater power to rotate and advance, raising energy consumption. Greater mass and inertia also increase energy spent during start/stop cycles and transient conditions.

Thinner walls: Lighter rods typically reduce running power demand, offering theoretical energy savings. In practice, however, the higher incidence of deformation or damage with thin rods can cause frequent stoppages and replacements; the resulting repeated starts and operational interruptions produce inefficient energy use that can offset the light‑weight benefits.

Conclusion and optimization guidance There is no universally optimal wall thickness. Selection must balance formation conditions, required drilling precision, production efficiency and budget. Practical approaches to optimization include:

Match thickness to formation and duty: use thicker, higher‑strength rods for hard, abrasive or unpredictable strata; use lighter rods where formations are soft and handling or energy constraints dominate.

Improve material and manufacturing quality: select higher‑strength alloys or heat‑treated steels and ensure tight concentricity and dimensional control to allow lower wall thickness without sacrificing performance.

Preserve flushing capacity: design internal diameters and flushing ports to maintain sufficient cuttings transport when choosing thicker walls; adjust flushing pressure and flow accordingly.

Reduce start/stop penalties: plan operations and maintenance to minimize unnecessary stops; use robust inspection and predictive maintenance to avoid sudden failures.

Use auxiliary measures: centralizers, stabilizers and proper bit selection can compensate for reduced stiffness; corrosion and abrasion protection (coatings, internal liners) extend life for thinner rods.

Implement strict inspection and tracking: serial‑numbered tracking, regular non‑destructive testing and condition monitoring help catch concentricity defects, internal wear or lubrication issues early.

By weighing these trade‑offs and applying targeted measures, operators can select a wall thickness that achieves the desired balance of safety, accuracy, efficiency and cost for their specific drilling context.